BEATRIZ SIMÓN: DOMESTIC CLEANING AS ART

by La Consultoría

Mexico City, June 2022

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

Beatriz Simón, Nam Mopping, 2014. Artist’s studio, Mexico City. Photo by César Palomino.

As a member of the fourth generation of La Consultoría’s educational program, Beatriz Simón (Mexico City, 1962) developed a project that ignites tension between domestic chores and art. Through extensive collective work, a group of homemakers provided the artist with approximately 16 pounds of dust from their homes —accumulated from their daily cleaning activities— as well as dirty rags and fretted fiber. Simón subverted the painter’s role by replacing this discipline’s traditional oil paints and acrylics with domestic materials, contributing to the history and legacy of artists who have explored the relationship between art and domestic cleaning during the last century. For the most part, these artists have approached the issue from a gender perspective by raising questions about the social constructs that have permeated the art world and the way in which we relate to it. By sharing some examples from domestic work in art history, as well as the questions that these works address, we will gain context for a better understanding of the lengths and implications that the artist’s pieces have set in motion in dismantling pictorial language.

Painting posing as a naked woman

One of the first introductions of dust in an artwork was in La Mariée-mise á nu par ses célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even), by Marcel Duchamp, popularly referred to as Grand Verre (Big Glass). Initiated in 1912, the creation of such a piece required eleven years of work, however it was still declared “definitively unfinished” by Duchamp in 1923. La Mariée… is composed of oil, varnish, lead sheets and thread, and the dust from the studio in which it was created. All of it compressed between two broken glass plates divided into two panels, one on top of the other, with five strings of glass, an aluminum plate, and a wood and steel frame. Inexpressive and mechanical drawings can be seen in the two panels of the art piece representing what the French artist described as the erotic process between the desire generated by the bride (in the upper panel) and her bachelors (represented by the mysterious machineries that can be seen in the lower panel).

Marcel Duchamp, Grand Verre, 1912-1923. Museum of Philadelphia.

The use of this undesirable domestic material is not the sole idea to highlight in the example described. Rather, it is the fact that Duchamp’s Grand Verre encapsulates the artist's metaphysical cosmogony about the erotic flow of life, the impulse between the desiring subject and its desire. In the French artist’s work, the latter is generally referred to through the use of a female figure —the bride— that arouses desire in the male characters. Four decades later, Duchamp revisited the same allegory in his last project, Étant donnés… (Giving Itself…) (1946-1966). This installation presents a morbid scene which can be seen through a peephole in a door bolt: a naked woman with legs spread, lies on top of a table among a pile of dry grass and dead leaves, appearing abused and abandoned, decadent, yet holding a lit gas lamp in her left hand. The scene is set against the background of a bucolic pictorial landscape with a simulated waterfall. The portrayal of the nude female and the background landscape suggest an allusion to the language of painting, where the genres of nude and landscape are widely known. Speculation has surrounded both the artist's intentions and the montage’s meaning since its first public display in 1969 —the year of the artist’s passing. However, some ideas surrounding the artist’s work have consistently emerged that Duchamp built an allegory foreseeing the death of painting itself, or at least, a declaration of the predicted expiration of this centuries-old discipline, that until the beginning of the 20th century had been predominantly used in the West to represent naturalistic scenes.

Marcel Duchamp, Étant donnés…, 1946-1966. Museum of Philadelphia.

The rise of feminist theory led to read Duchamp’s Étant donnés and his other works primarily involved criticizing the representation of the female body as an object of desire. This extended to portraying the male figure as one yearning for female purity, virginity, and their sexual availability. Most notably, criticism was directed towards Duchamp equating the painting itself to the female gender. In Étant donnés, the painting appears as a violated and relinquished body, spied on voyeuristically through a peephole. This act represents an exercise where the viewer’s experience clearly resembles that of a male subject peering in order to satisfy his curiosity and desire. From this perspective, it appears evident that the art world was shaped in accordance with dominant gender constructs, whereby the feminine —the painting or work of art— is seen through a male gaze —the spectator. This relationship established a clear connection between painting and gender, one that emphasizes the influence of the male gaze in perceptions of art.

Cleaning the art world

The feminist art movement developed in parallel to what is now referred to as the second wave of feminism in 1960s America. One of the main characteristics of this second wave was advocating for the recognition and importance of spaces that used to be considered “private” such as one’s home, family relationships, and motherhood, extending to birth control and women’s sexuality. In 1970, feminist theorist and artist Kate Millet authored the book Sexual Politics, which would become a referent in gender discussions and reflections for years to come. Millet’s coined phrase “What’s personal is political” was adopted as both a slogan of protest and as an artistic expression once the feminist fight started focusing on the domestic and private spaces of everyday life.

This movement gave birth to, in 1971, a pioneering feminist art program at California’s Institute of the Arts, led by Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro. This university program not only spread the idea of feminist art throughout the United States, but extended its impact to many other countries. The proliferation of this movement, coupled with the emergence of affordable, ephemeral, and unintimidating new conceptual media (such as video, performance, photography, narrations, texts, or actions), encouraged women’s active participation in the art world. The female perspective gave art a fresh approach, exploring artistic questions that hadn’t yet been traversed. Such themes of exploration included: the narrative, distribution, and interpretation of social roles; notions of appearance and disguise; matters surrounding beauty, the female body and its biological processes; as well as the invisibility of domestic work. Through their practice, feminist artists also tackled issues of fragmentation, affective relationships, autobiographies, everyday life, and of course, feminist politics. In addition, Chicago and Shapiro’s feminist university program conceived the relation between art and domestic chores in its first group exhibition held in 1972, titled “Womanhouse”. This title serves a direct allusion to the historic marginalization of women in domestic, private, and family spaces.

Art critic and historian Lucy Lippard reflects that during the seventies, thanks to the liberal politics adopted by many male artists, the possibility of unprecedented support for the feminist program seemed more attainable. Lippard highlights that, in those years, some male artists actively supported the Ad Hoc Women Artists Committee project, a branch of the Art Workers Coalition, in challenging the Whitney Museum’s annual exhibition in New York City. During this event, an “anonymous” female group forged the museum’s press release, claiming that the exhibit would showcase 50% artworks by women (with 50% of that by women of color). Fake inauguration invitations were then distributed. On the day of the annual exhibition, a projector was used to display a slideshow of female artists and their artworks on the museum’s exterior walls. This prompted the arrival of the FBI on site, initiating an investigation and search for those responsible.

During that same period, artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles posed questions about the exclusion or inclusion of domestic chores within the arts. Laderman studied art at New York’s Pratt Institute in 1962, where she produced a series of sculptural paintings featuring abstract, abject, and voluptuous motifs. These pieces caused a scandal among the school’s administration, who described them as “oversexualized” pieces. One of her teachers even resigned as a form of protest, and soon after, Laderman dropped out. She then enrolled in an art program at the University of Denver, where she continued producing her art series. In 1966, Laderman married, and two years later, gave birth to her first child. This life change brought her to a feminist crossroads, as she wanted to be both a full-time mother and an artist. Like many women before and after her, she struggled with the challenge of finding time for both roles. “I literally had to split myself in two”, she told Art in America in an expression of her inner battle, “I would be a mother for half the week, and an artist the other half”. Inspired by this experience, Laderman did what any dedicated artist would do: she wrote a manifesto.

The Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! Proposal for an exhibition ‘Care’ is a three-page typewritten document by Laderman that is divided into two parts. In the first part, Laderman distinguishes between what she calls two basic systems that reflect social and gender constructs: development and maintenance. The former is associated with the vanguard and is implicitly linked with masculinity. It centers on individual creation, progress, change, advancement, novelty and excitement. The latter, Maintenance, refers to tasks generally associated, especially with the domestic sphere, with women and household chores, including cleaning and preserving the original creation, protecting progress, maintaining change, defending and prolonging the advances, preserving what’s new, and renovating what’s exciting. Laderman highlights a significant problem: society values Development, while Maintenance is consuming and “takes all the fucking time”. Her proposed artistic solution is to merge the two systems by “creating an exhibition that only consists of Maintenance, showcasing it as contemporary art.”

The second half of the manifesto outlines Laderman’s exhibition proposal —titled “Care”—, organized into three sections: “Personal”, where the artist performs household chores inside the museum, instantly elevating these actions into the (higher) status of art; “General” featuring interviews with the audience about their relationship to maintenance tasks; and “Earth”, focusing on repairing and recycling various types of waste delivered to the space. Despite submitting the proposal manifesto to various institutions, it was rejected by all and the exhibition never took place.

Regardless, the artist carried out personal acts at her home, which she documented for public presentation. Examples include Rinsing a B.M. Diaper (1970), where she washed a diaper, and Dressing to Go Out/Undressing to Go In (1973), where she dressed her son in suitable clothes for indoor or outdoor activities. Labeling these actions as art was a radical feminist and Duchampian strategy, with Laderman citing the French artist as an influence on her work. The artist also brought her reflections to art institutions, where the personal meets the public sphere. In Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside (1973), documented in a series of black-and-white photographs, the artist is seen cleaning the steps of Wadsworth Atheneum, holding a mop like a brush, splashing water, and scrubbing the pavement with a rag. Toward the end of the 1970s, Laderman expanded her practice by collaborating with New York City’s sanitation personnel, creating iconic pieces such as I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day (1976) or Touch Sanitation Performance (1979–80).

Following the same idea, in 1977, the feminist collective Mother Art presented performances across five laundromats in Los Angeles, California. Throughout the duration of each wash and dry cycle, the Mother Art artists would hang their work on clotheslines. Using the washing machines as background noise, they performed the ritual of folding clothes while wearing paper masks shaped like clothespins. Gloria Hajduck, a member of the Mother Art collective, explained the purpose to a local newspaper in 1979, “We wanted to show people that art is not only found in a Van Gogh painting, and that we can create art with everyday material in our quotidian lives.” The collective wanted to challenge the notion that art was limited to the traditional. They distributed pamphlets protesting against the invisibility of tasks traditionally denominated as women's tasks: highlighting disregarded domestic and emotional work, from family care to the undervalued, unnoticed, and underpaid routine domestic chores. Mother Art carried out other public art projects to emphasize the significance of maintenance work. In the mid-70s they launched a “cleaning campaign” in which they washed the facade of public and institutional buildings, including Los Angeles City Hall.

Dismantling pictorial language through domestic cleaning work

It is on this genealogy that Beatriz Simón builds her artistic proposal, addressing the unresolved matter of painting and its relationship with domestic cleaning. She explores it through an abstract language, intertwining it in conjunction with the historic implications such an examination entails. In her current production, the artist approaches pictorial abstraction in a non traditional manner. Rather than emphasizing the absence of meaning and references that prevail in order to achieve visual purity through traces, gestures, expressions, colors, or compositions, she introduces a new dimension. Simón defies the language of painting, contaminating it with elements that the discipline has eluded and excluded for centuries: domestic chores. This opens a dialogue that reimagines gender in art, effectively dismantling the patriarchal constructions upon which the language of painting was founded.

Notably, the titles of the artist’s pieces draw from phrases that appear on contemporary cleaning products found in supermarkets. These product names have been designed with appeal to the high expectations of perfection regarding domestic work. It Cleans and Shines, Deep Cleaning, Double Cleaning Power, Cleaner Surfaces, For Rough-use Cleaning, and Extreme Cleaning, serve as examples for analysis in this section.

It Cleans and Shines (Exploration of texture) is a collage crafted entirely of metallic fret fibers, representing a strategy comparable to that of the readymade concept, first proposed by Marcel Duchamp. In using this approach, Simón deliberately removes individual expression from her paintings, avoiding the traditional act of painting as a creation of something original and unique. The artist’s decision to resort to readymade as an artistic strategy reflects a direct challenge to pictorial tradition. Duchamp introduced this method at the beginning of the century as an alternative to the conventional production of painted images, countering the myth of “original creation” that painting carried for centuries. This myth was mostly unchallenged until the mid-20th century, when artists like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter or Sigmar Polke, questioned it too (following Duchamp’s steps) through their work. The titles used in Simón’s series, as well as the chosen materials, are undoubtedly and intentionally readymades, alluding as well to the pop inclinations of the artists mentioned and engaging with their legacy in such a way to highlight the complicated relationship between painting and the readymade.

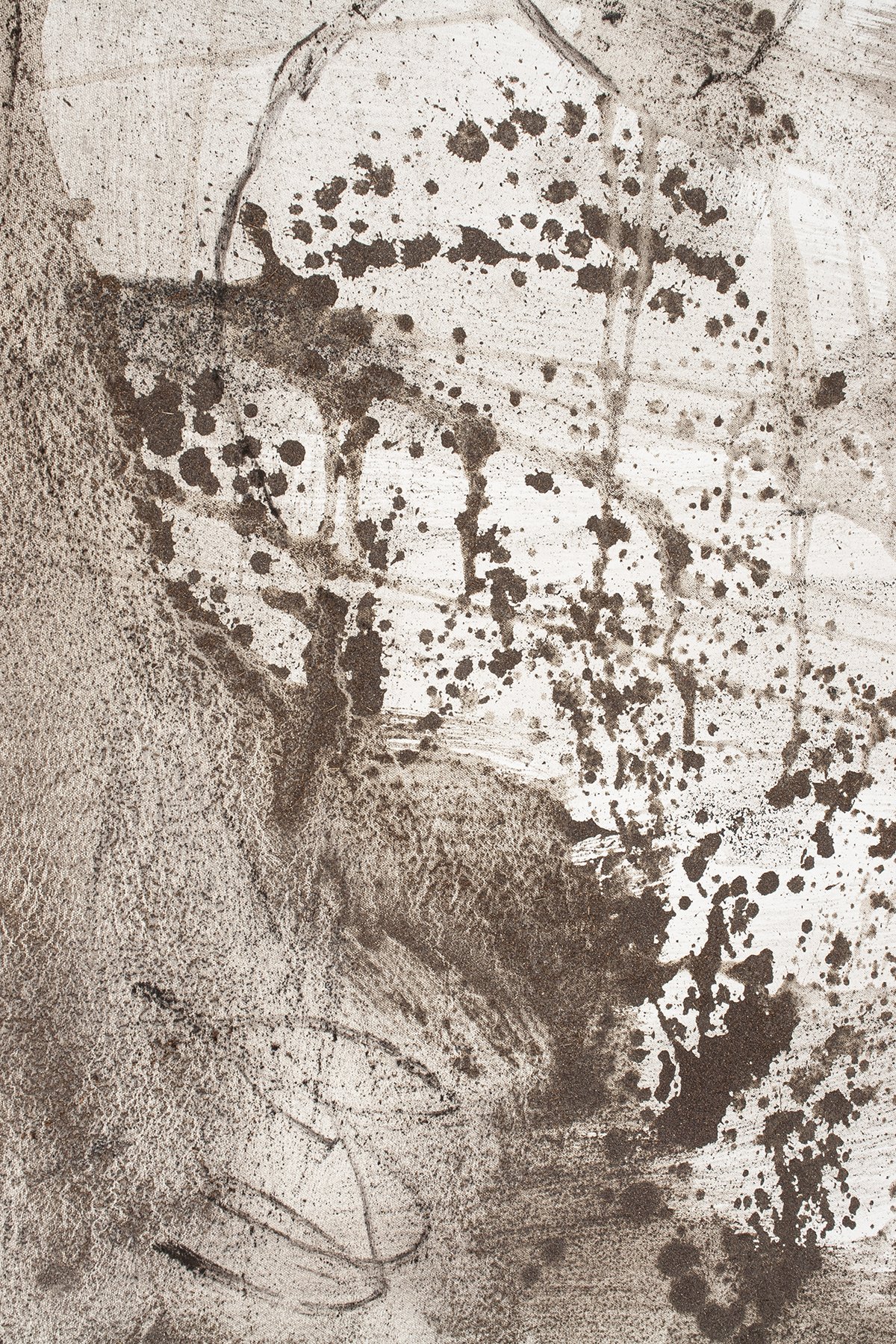

It Cleans Deeply (Lyrical Composition), on the other hand, portrays a closer relationship with the American abstract expressionism, highlighting the importance of brush strokes and the traces of paint on the canvas. What differentiates this work from the latter, however, is the material the artist uses: household dust, which restricts the color palette to a minimum, a range of neutral and earthy tones. In this way the artist achieves the darkest traces through the accumulation of lumps or fuzz. This exercise only simulates pictorial expressiveness, where the artist substitutes the traditional selection of paint colors and utilizes the natural qualities of the material itself instead. This form of artistic expression is one where the color palette is a byproduct of the readymade exercise, subverting the painter’s traditional role as a creator of tonalities and chromatic games with visual impact.

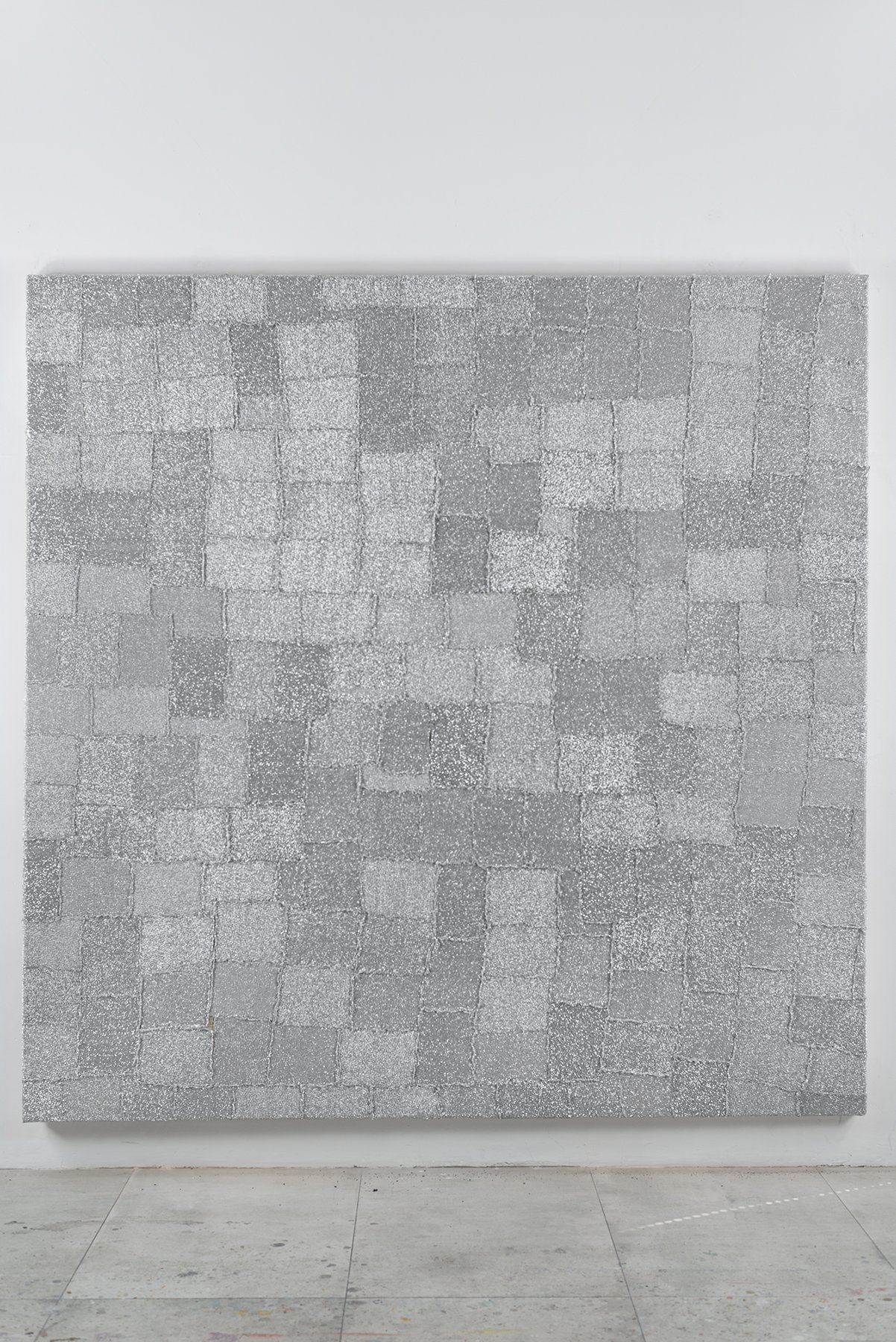

Beatriz Simón, Double Cleaning Power (Exploration of Texture), 220 x 220 cm | 86.6 x 86.6 inch, 2021. Artist’s studio, Mexico City. Photo by César Palomino.

Similar to other metallic fiber works, Double Cleaning Power (Exploration of Texture), draws parallels between the pictorial interests of creating textures and volumes from material accumulation. This particular collage was made from a single strip of metallic fiber, likely sourced in bulk, and stitched to the canvas from the outer edge of the canvas inward. This created a series of concentric squares with a metallic appearance. The resulting image and the method of production associate this piece with minimalism: the industrial origin of material and the geometric configuration excludes any attempt at an aesthetic composition typical of conventional painting practice. Thus, this work serves as a subtle reminder of the historical dispute between abstract expressionism and minimalism. Partly based on the latter’s response to the excessive and traditional pictorial art this piece reflects minimalist practice through repetition of geometric forms.

Beatriz Simón, Cleaner Surfaces (Natural Gray Field), 220 x 220 cm | 86.6 x 86.6 inch, 2021. Artist’s studio, Mexico City. Photo by César Palomino.

Cleaner Surfaces (Neutral Grey Field), essentially a neutral grey field painted with a single layer of color, portrays a fundamental and recurring motif that can be perceived throughout most of the artist’s recent paintings. It underscores a shift away from the traditional pictorial expressiveness, which is based on individuality and originality, toward a mechanical and repetitive expression typical of domestic chores. Regarding Cleaner Surfaces, the painting –or the staining– using a dust-stained rag, replicates the movement of the hand when cleaning a surface. The resulting shapes on the canvas reveal traces of this action. The substitution of brushes with rags can be considered a turning point in the historical development of painting, from which women have been systematically marginalized.

Beatriz Simón, For Rough-use Cleaning (Exploration of Texture), 220 x 220 cm | 86.6 x 86.6 inch, 2021. Artist’s studio, Mexico City. Photo by César Palomino.

It is clear that all aforementioned pieces embody a feminist perspective towards painting. Another example of this perspective is For Rough-use Cleaning (Exploration of Texture), a variation of the metallic fiber collages. In this piece the fiber reflects one of its applications —to remove the most difficult stains from dishes— through its round shape and curled texture. Contrary to previous metallic pieces, this texture produces a more aggressive, organic, and sinuous form. In the same way that Mierle Laderman Ukeles proposed in her manifesto, advocating for the performance of household chores inside the museum to elevate them into art status. The coalescence of domestic materials into the pictorial space of Simón’s work not only turns them into paintings, but by doing so it also challenges the limits between what can be considered painting and what cannot.

Through this strategy, Beatriz converts into a pictorial language what art has historically marginalized: the mundane tasks and the domestic chores to which women have been socially relegated to for centuries. The artist’s paintings disrupt the expectations that have been imposed upon women and their place in the art world —from being recognized as nude models and (male) artists’ muses—, to becoming creators in their own right, and to having the freedom to decide what painting can become from now on. In other words, through her work, Simón redefines and broadens painting as a practice not limited by gender and social constructs, but rather an inclusive form of expression.

Another notable characteristic inherent in the artist’s work is the collective nature of the process through which the paintings were created. An illustrative example of this is the production of Extreme Cleaning (Exploration of Texture), where a group of 50+ homemakers donated dust from their homes. The dust was collected for weeks as a result of their daily cleaning chores and a total of 16 pounds of material was accumulated. Most of this matter was allocated for Extreme Cleaning…, since the artist’s interest was focused on gathering an exaggerated accumulation of dust in order to investigate the tactile possibilities over a canvas. This collaborative process between women reminds us of the solidarity that has characterized feminist associations and movements since their beginnings.

One more interesting feature of Extreme Cleaning (Exploration of Texture) was the intense odor that resulted from the combination of dust, water, and acrylic. Interestingly, this aromatic dimension led to an unintentional allusion to Duchamp’s curiosity for odors, as they represent a dimension that eludes visual representation. Unlike the aromas related to desire and referred to by Duchamp in his works, such as chocolate or coffee, the smell that emanates from Extreme Cleaning… does not cause desire; rather, it repels the spectator, subverting the feminine role that is expected to seduce the spectator in a traditionally masculine way.

Beatriz Simón, Hanging Cleaning Fringe (Antiform Exploration), 220 x 280 cm | 86.6 x 110.2 inch, 2021. Artist’s studio, Mexico City. Photo by César Palomino.

The last worth mentioning example would be Hanging Cleaning Fringe (Antiform Exploration), a painting where a series of dirty mop threads (previously used to clean the artist’s studio) hang from the top of the frame until they hit the ground. This piece reflects Simón’s interest in exploring the sculptural qualities of painting, an inclination similar to that of the post-minimal artist Eva Hesse. Hesse investigated the possibilities of minimalist sculpture with flexible materials such as ropes and knots suspended in space. The reference to Hesse, coupled with the use of bulk materials and the reduction of the pictorial palette to neutral tones and simple forms, emphasizes Simón’s affinity for a post-minimalist language. This can be explained by the fact that post-minimalism posed a feminist distance by diverting from the masculine minimalism of the late 1970s in the United States, which excluded the female perspective from sculptural practice, and was later criticized by feminists in the following decade.

In conclusion, Simón’s pictorial research on household and domestic chores uses daily (and repetitive) cleaning rituals to reveal what remains after the dust has been cleaned: a tradition of exclusion and rejection that has been exercised towards the female gender from all aspects and spheres of life, from art institutions to the smallest corners of our bedrooms.

Beatriz Simón, Hanging Cleaning Fringe (Antiform Exploration) (Detail), 220 x 280 cm | 86.6 x 110.2 inch, 2021. Artist’s studio, Mexico City. Photo by César Palomino.

Resources

Jorge Juanes, Marcel Duchamp: Itinerario de un desconocido, Ed. Ítaca, Mexico City, 2008.

Lucy R. Lippard, “Intentos de escapada”, in Seis años: La desmaterialización del objeto artístico de 1966 a 1972, Ed. Akal, Madrid, 2004.

Jillian Steinhauer, “How Mierle Laderman Ukeles Turned Maintenance Work into Art”, in Hyperallergic, February 10th, 2017. Available online.

Sarah Wade, “Mother Art and the Politics of Care”, in Getty/News & Stories, April 8th, 2021. Available online.